The Question with No Answer

or, The Divinity of Doubt

Readers should note that the Holocaust will be discussed in the blog post below. It is important that stories are told so that the same horrors are never again allowed to happen to anyone. There is no graphic detail, but this may not be the best light morning read. Discretion is advised.

Thank you for your patience through the last few months’ hiatus! I’m grateful to have seen that we have a number of new subscribers and quite a few returning ones who caught up on our series!

Our journeys in Active Imagination continue.

The Personal Journey

As you recall, we last followed the journey of the Ronin, a Samurai without a master. A very archetypal figure, his tale echoed elements of Zen teaching, finding peace in apparent paradox.

The Problem of “I”

The Warrior Without A Master The next figure the we encounter in The Tree J. Marvin Spiegelman’s journeys in active imagination, is known as the Ronin. This Japanese term refers to a Samurai (commonly translated as “warrior,” but more literally translated as “servant”) without a master. A Samurai would typically become a Ronin (from “ro” meaning “wave,” …

We continue our journey in the Jungian practice of Active Imagination through J. Marvin Spiegelman’s The Tree, with our next guide, Julia, the Atheist-Communist.

That Julia is quite different from our previous guides is instantly apparent; she is the first woman, as well as the first guide to have a name, and her title, the Atheist-Communist, places her as a firmly modern figure. Her story is told in a series of seven-year intervals which makes it far more biographical than either of our previous three guides as well.

Julia is somewhat of a sister to Spiegelman; like him, she is a Jew born in 1926. Each is personally affected by the Second World War in different ways determined by the manner of their births (Spiegelman, born in Los Angeles, served in the United States Navy, while Julia’s birth in a Polish village meant that the war came to her.) Perhaps this session in Active Imagination is so different and personal because Spiegelman imagined himself in a life that could easily have been his under different circumstances.

Where Julia’s journey is a personal one, it is her family that fills more archetypal roles. Her Zaideh, or grandfather, is an old, wise, and long-suffering man described like a Patriarch of old. And her father is a Communist true believer in the vein of the New Soviet Man, looking to the east with optimism for a new world and a liberated working class. In a sense she is torn between the two primary male figures in her young life as she is torn between visions of the past and of the future.

My grandfather would say about Karl Marx: “A Jew who is not a Jew! Who ever heard of it! Paradise of Earth, yes, but without God? He has it all upside down! Too much goyische [gentile] thinking in his head!” To which my father would answer, defensively: “All your religion, all your Jewishness has brought the Jews nothing but pogroms, pain, and poverty! Where is your God at pogrom-time? No, we must make Paradise on earth, but we, men must make it, and not wait for some Messiah to come on his white horse!”

But there is a surprising harmony in Julia’s small forest village, as her family cares for each other in a way that is reminiscent of both the Patriarchal and Communist ideals. Despite their outward opposition, in secret Julia’s father expresses his admiration for the egalitarian compassion of her Zaideh, and Zaideh admires her father’s belief in a better world to come despite his atheism.

Yet this strange state of paradise would not last; as the first seven-year cycle of her life closes in 1933, her family splits due to the Great Depression. The traditionalist Zionists await their deliverance in the forest, while the progressive Communists move to the new setting of the city.

Fall From Paradise

This marks the point of disintegration in Julia’s reality. The modernity of the Polish city stands in stark contrast to the idyllic life of the forest village. Julia and her father are second-class citizens, harassed for their Jewishness. Her father smokes heavily – inhaling the nicotine of manufactured cigarettes, as opposed to Zaideh’s puffing of pipe tobacco – and she becomes melancholic.

Julia must confront her suffering when her father dies to lung cancer, and she turns to Zaideh. Hoping to encounter the great faith of Abraham Julia instead sees the profound suffering of Job, a deep sadness behind Zaideh’s eyes. She does not see a man who has the answers she would ask of God, and her faith shatters.

The problem of suffering has long been debated in the minds of theologians and in the hearts of believers. While suffering was confronted earlier by the Knight in a metaphysical sense, Julia’s experience is a far more lived, human one.

The Knight's Quest

The Call to Adventure The first guide we meet in Spiegelman’s journeys in active imagination is a medieval European knight, wearing black armor emblazoned with a golden sun. The Knight becomes the narrator and subject of the active imagination session that ensues, beginning with the image of a vicious King living in a hollow shell at the bottom of the se…

While Julia and her family avoid the German invasion of Poland and the Holocaust, fleeing the increased anti-Semitism that fueled Hitler’s rise. Yet she is deeply affected by the suffering of her people.

It is challenging to approach, but Julia’s atheistic response to her father’s death and her people’s persecution is representative of the experiences of many during that time. Writings on the walls of the Mauthausen concentration camp, which primarily imprisoned gentile partisans and intellectuals but also held a Jewish population in later years, exemplify this in messages such as: “My God, why have you forsaken me?” (the opening line of Psalm 22 as well as the last words attributed to Christ in the Gospel of Matthew) and “If there is a God, he will need to ask me for forgiveness.”

It is no wonder that the problem of suffering is faced so deeply by Julia. Through her Jewish family she is part of a tradition which has provided purpose to generations of her ancestors, yet is silent in the face of her suffering. She asks the questions that, as explored in Andrew Brown’s fantastic article for The Guardian1, are often forbidden as there is no satisfactory answer.

To any reader familiar with Spiegelman’s other work, I would like to hear if this is something that he addresses in his book A Modern Jew In Search of a Soul. His unconscious clearly resonates with this dilemma, and I am curious to hear him address it more directly.

The Unanswerable Question

The end of the second seven-year cycle of Julia’s life coincides with the height of the Second World War. Her first period comes on September 1, 1939, the day that Nazi Germany invades Poland. Julia’s immediate family, much like Spiegelman initially did, witnesses the war from afar in the relative safety of the United States. But when the war ends, and the full extent of the Holocaust is discovered, her grandmother (Bubeh) dies of grief for the family left behind.

Julia asks Zaideh how there could be any meaning to the suffering, and he cannot answer; they embrace each other in tears together. The old patriarch’s faith is not shaken and the young Communist’s is not restored, but they share a moment of not having the answers together.

That night, Julia has a dream. Any dream in a Jungian work should be taken very seriously, as a window into the unconscious. Much like the practice of active imagination, dreams are not bound by the laws of rationality or limits of physicality, and allow the unconscious mind to express itself in the raw language of symbol.2

In her dream Julia feels the pressures of the earth all around her and digs her way to the surface to a glimpse of her family. But she cannot rest with them; she continues to be pulled upwards until she finds herself before God.

Now I was more frightened and angrier. I was unbelieving, and thinking this a trick. Then I changed; in the dream, I changed: I decided to bring my complaint to God. I decided that I would rise up to God and complain to Him about how He treated Man, how terrible He had been to His Chosen People, and how He was not entitled to be worshipped and prayed to by the people, and how I no longer believed in Him, anyway.

With this infusion of anger, of questions, firmness, and rage, I heard a Voice. It said: “She speaks truly of the Lord, listen to her.” I found myself sinking back to the earth, gently, easily, until I found myself safely resting in my bed.

Though she does not yet understand it, Julia’s unconscious (and by proxy Spiegelman’s as well) grants her the first hint of integration, that she may have her doubts and even atheism fill a role in the divine tradition embodied in her Zaideh. As we shall see, this gift from her unconscious also brings Julia closer to realizing the utopian dreams of her father.

As the third seven-year cycle of her life comes to a close in 1947, Julia moves to Israel to chart out the next stage in her development, embracing the paradox of being a Jewish Atheist for God.

Our next post will be the conclusion to Julia’s story, and includes a meeting with Carl Jung himself.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2014/jun/16/god-auschwitz-otto-dov-kulka-religious-belief

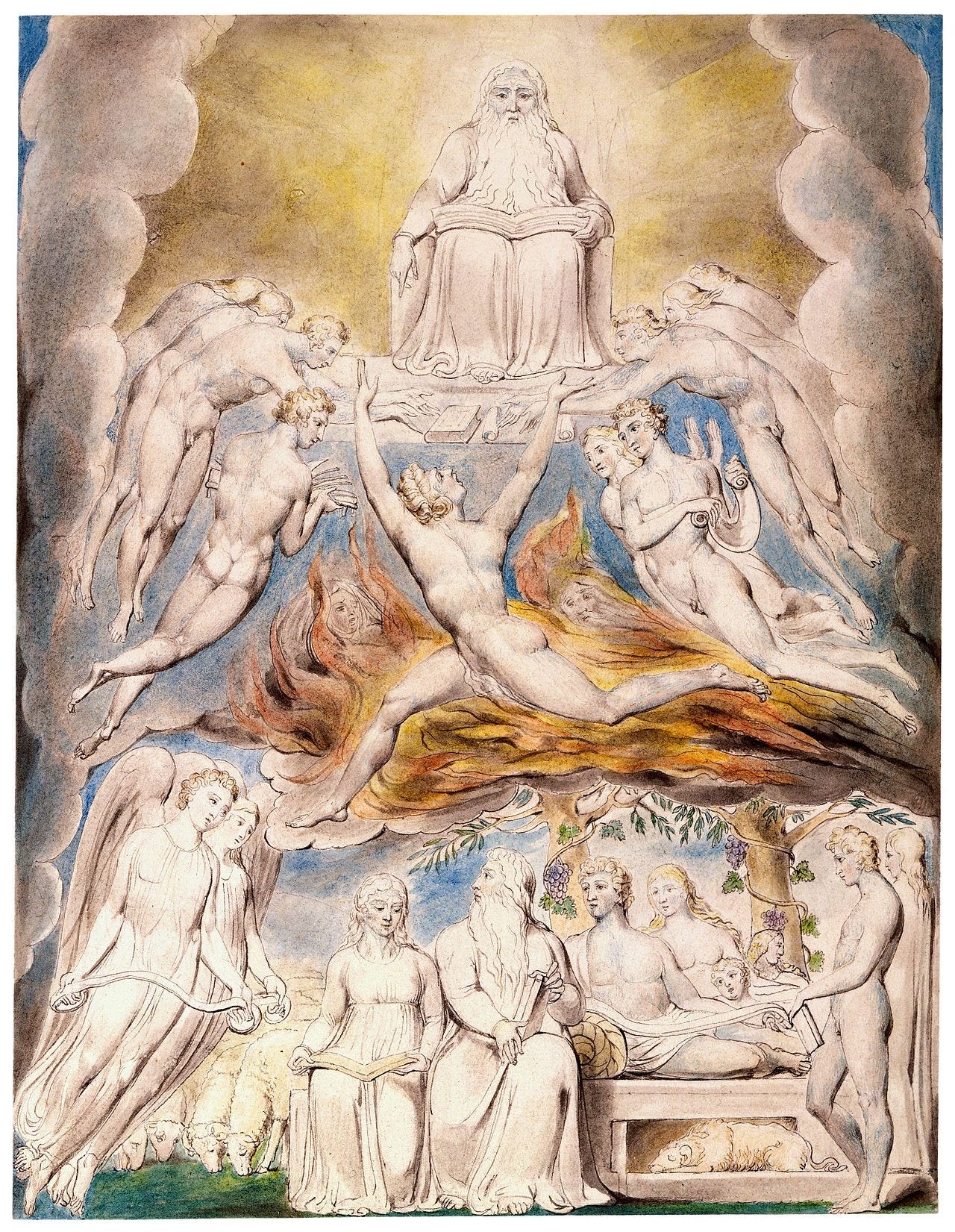

Image: Satan Before the Throne of God by William Blake from Illustrations to the Book of Job

These are such deep topics for reflection, as all of Spiegelman's active imagination "Journeys". Ideas like blessings, Grace, gratitude etc. will understandably come under increasing pressure and doubt as personal suffering reaches a certain threshold. Or indeed for a whole people. That people still keep faith and belief under such circumstances is humbling to deliberate.