Solving the Problem of “I”

or, Understanding the Ego through the Soul

The Mysterious Beast

When we last left our Ronin, he had retreated into the mountains. He had set out to remove himself from the praise and scrutiny of others, and decided to confront the core of the issue – his Ego – alone.

But the Ronin quickly turns back – not out of resignation, but a realization.

I was alone and I was lonely. This was a shock to a man like myself who had been very used to thinking of himself as a lone one, who can wander the world without need of anyone. Ha! I thought, this is salutary in itself – I must have been attached to the idea that I am alone and a lone one. My secret desire for fame and recognition is no better and no worse than this secret illusion that I can be utterly non-attached to people.

The Ronin returns to society without the enlightenment that he had hoped to find, but with a better understanding of himself as a being with desires and needs. Even his desire to retreat from others is just that, a desire. The Ronin’s task of separating himself from the outside world to confront his Ego still originates from that same Ego, the “I” that speaks when he says, “I will retreat into the mountains.”

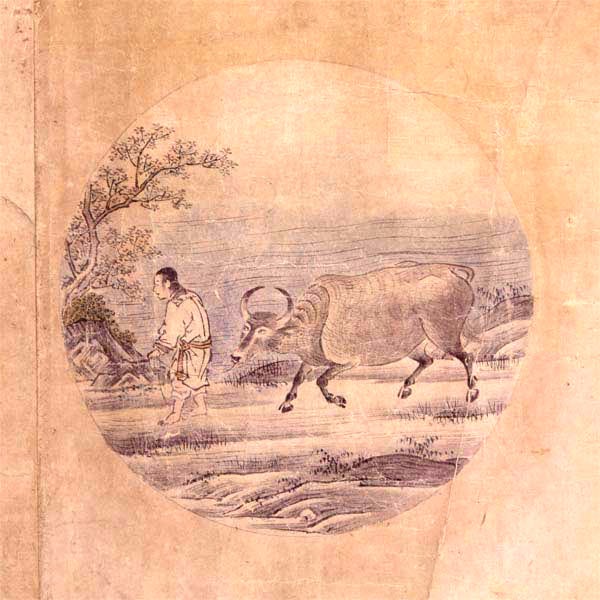

But the Ronin is pleased with this small victory, that he can now recognize his desires in their many forms. In an episode of active imagination, the Ronin sees his soul in the image of a black bull. It is a bull that he has struggled with for years, attempting to tame it with whips and ropes. When the Ronin gives up in exhaustion the bull runs wild, chasing its whims with a trail of chaos behind.

Yet with the acceptance that his drive to tame the bull is rooted in desire, just as the bull’s wild whims are, the Ronin sees something different. Simply by acknowledging it, the wild, black bull begins to calm itself and turn white. To the Ronin, the bull is like a koan, a paradoxical Zen riddle. The bull whitens because the Ronin accepts it, and he accepts it because it whitens.

The Bull and the Rider

The Ronin walks side-by-side with the bull for a time, knowing that he cannot yet mount it. But rather than force it into submission, he walks with a loose grip on the reins. He listens to the bull and it’s cries, and notices that its acts are not as mindless as they seem. When it runs for water, it is because it thirsts. When it cries out, it is because it has been hit. Though he cannot always understand it, the Ronin comes to recognize that the bull has its own desires and needs.1

Often we do not recognize what our souls desire. Especially in the Jungian understanding of the unconscious mind as host to a myriad of archetypes and personae, understanding their needs can be a grand challenge. Understanding the desires our inner masculine and feminine (Animus and Anima;) our innocence and experience (Inner Child and Wise Elder;) and the “darker” or lacking sides of each (Shadow) are each a grand task – and that list is not exhaustive.

The Ronin’s acceptance of and listening to his bull prescribes listening and understanding as the first step. If we can recognize and be mindful of what we actually do want, our Ego does not need to be opposed to the desires of these other parts of the Self. Where lashing out is unacceptable (like the proverbial bull set loose in a china shop) acknowledging the soul’s needs provides the opportunity to meet them in a healthy way.2

In time, the Ronin is able to ride through town on the back of his bull, singing a joyful song of their unity. And accepting the needs of his soul shows the path forward for addressing his Ego.

The Ego Transcended

The Ronin is able to live in peace for a time, having mastered the wild animal inside.3

But then it hits him – is it not the Ego which has crowned itself as master? Even in saying, “I have made peace with the animal which is my Soul,” the inescapable “I” remains ever-present. How can the Ronin truly be a master when the Ego still remains?

The Ronin wonders if his task is impossible. It was the Ego which led him to master the sword, and even Ego that led him on the noble task of mastering his soul. But still, that Ego cannot be escaped. Even if he were to end his own life, it would be the Ego making the decision.

The key to solving this issue comes in re-examining his relationship with the bull. He could neither discipline nor ignore the mighty beast, but only walk by its side. Could he not do the same for his Ego?4

Just as he was able to acknowledge the needs of the bull, the Ronin acknowledges the needs of his Ego. And he finds the same result; the more he acknowledges it, the tamer is becomes. And just as the rider is able to transcend the bull, the Ronin is able to transcend his Ego, viewing himself as a part of the world just as the bull is a part of himself.

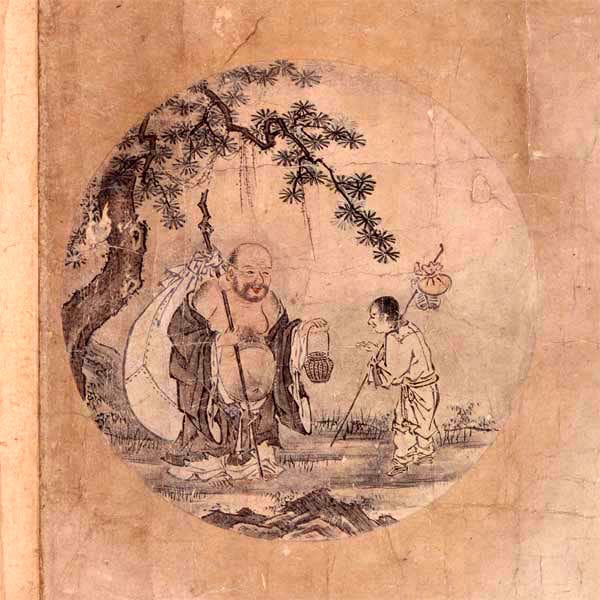

It is with this realization that the Ronin is able to join our other guides at the Tree of Life. While the soul cannot be controlled, it can be listened to. And while the Ego is ever-present, it is not everything. The Ronin’s story closes with a song, celebrating the greater existence of which he is a part, celebrating “the great little ‘I’” which loves “the wicked little ‘I’.”5

The Ronin sings of a tree in the forest which splits in two, only for its trunks to grow round and meet again; at once an empty hole and a full whole. He sings of a flower blowing in the wind, holding onto its petals, loving itself just as its roots love and hold onto the ground.

The Ronin’s story ends with him returning to his friends and enjoying them more than ever. They did not even notice that he had gone, and the Ronin now is able to see in each of them, like himself, the nature which they all serve.6

The Ronin’s story, like the traditional Zen motif of the Ten Bulls that it follows (and from which the accompanying illustrations come) takes the mysterious journey of enlightenment and brings it to a personal level. It is fascinating to think of how each of our guides found themselves around the same tree, despite the vast differences – materially and symbolically – in their journeys.

Each of our guides up until now has undergone a very personal journey, with their explorations of the Self central to each narrative. The settings for these active imagination sessions have ranged from esoteric (the Knight) to worldly (the Arab) to traditional (the Ronin;) but still each has been an exploration within for our guides.

The same will be true for our next guide, though she will differ much from the others. Not only is she the first woman, and the first named character, she is the first to occupy a very distinct place and time. Our next journey will be with Julia the Atheist-Communist, a Polish Jew living through the Second World War.

As a note from this article’s author: The tragic and recent background of Julia’s story make for a more difficult read (I tend to prefer the archetypal figures of mythology over specific fictional or lived experiences) but I am hopeful at knowing that she, like our other guides, finds a meaning which brings her to the base of the same Tree of Life.

Image: Taming the Bull from Kuoan Shiyuan’s Ten Bulls, illustrated by Tensho Shubun

Image: Riding the Bull Home from Kuoan Shiyuan’s Ten Bulls, illustrated by Tensho Shubun

Image: The Bull Transcended from Kuoan Shiyuan’s Ten Bulls, illustrated by Tensho Shubun

Image: The Bull and Self Transcended from Kuoan Shiyuan’s Ten Bulls, illustrated by Tensho Shubun

Image: Reaching the Source from Kuoan Shiyuan’s Ten Bulls, illustrated by Tensho Shubun

Image: Return to Society from Kuoan Shiyuan’s Ten Bulls, illustrated by Tensho Shubun

Interesting food for thought - wonder if Spiegelman had any growing personal insights through these "mind-wanderings". He seems to maybe develop a better relationship to his inner life in this story, and a more flexible/less controlling way of relating to himself. Maybe focusing on an "open-ended" context is helping him. The self-mastery through the right brain. The more undefined frame of the bigger picture.